She tells me this story early in the morning. It isn't the first time she had told it to me, but her voice moves like a dancer, and I love to listen.

"When I was a girl, there wasn't more than this room. Our entire world, a room just like this one. Only, when we looked out the window, it wasn't this lake or this sky. When we looked out the window, it was grey, and the windows, endless, of the building across from ours. It wasn't your eyes I looked into, it was my father's. And I was smaller, much smaller, and I didn't know that you existed. But my father existed. And my mother, and my brother, Piotr. Piotr always wanted to play. Nine floors down, he would run down, call up to my father from the street, run back up, and jump onto his back. But father never left the room. He would send me out, since I was the oldest, to pick up our bread. Four rations of bread, and I would bring them home proudly. In those days, where I am from, that was what we ate. Not family dinners around the tv, but bread broken into pieces, around the radio. When rockets or guns would happen outside, mother would close the window, and the world would disappear behind a black curtain. He was a big man, my father. Bigger than those rockets. Bigger than that building, and certainly bigger than that room, or this one. He had patches of hair on his shoulders. 'That is what makes him great,' my mother said to me, 'that is what makes him strong and brave, like a bear.' But he only said, 'Nonsense. That is just the way that some people are.' He was always like that. Everything he said always made sense. Pretty soon he never went out at all, unless it was late at night. I wouldn't have none he'd gone at all, except I would wake up to the smell of eggs cooking, and he would be sleeping at the foot of the stove. Piotr always ate more eggs than I did. Piotr ate more eggs, and became bigger and stronger, and soon he was running with me to collect our bread, and then running past me, and returning home with the bread, without me. 'Piotr should get the bread on his own,' my mother argued. 'He's faster, and they are shooting at children.' Father never argued with mother. He would only look at her, and a decision would be made. No words spoken. From that day on, Piotr ran for bread alone."

I kiss her as she is telling me this, inside of her knees and elbows. But some stories are too good to be distracted by kisses. She lights the candle that she keeps beneath the photograph of her family. "I am going to tell you the end of the story," she said. I had never heard the end of the story. The end of her family.

"Piotr made Mother proud. He was a finder. When I ran for bread, it was always 'bread, bread, bread,' and nothing else on my mind. But Piotr was a different kind of creature. Things that caught the sunlight, things that made noises he had never heard, a dog with three legs instead of four- all of these things took the place of bread. And often, he would bring them home with him. Usually, it was something small, like a ball of tin or half of a chocolate bar. Things we could use. 'You've done well, Piotr," Mother would say. Father would say nothing. He prayed constantly for Piotr, because Piotr needed to be prayed for. There were bullets and bombs and rockets, all eager to find a boy like Piotr. There were things we didn't know about Father. Why was he so quiet? Why did he never leave? Why didn't he fight, like the other fathers in our building? Was he a coward? I never asked these questions, and I still don't ask them. I was happy that he was there, his big arms and his hairy shoulders, and his shirts that smelled like the mechanic's shop...

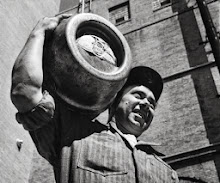

Piotr took a long time to get the bread. Mother was often certain he was dead, a little boy who got caught up in a big war. His body would be pummeled by concrete and buried along with the city that used to be beautiful. But Father would always look into her eyes, and we would all know that Piotr would be home soon. Until the day that he didn't come home. It was dinner time, and we were hungry. Mother kept a piece of bread every day, in case something like this happened. But it was stale and it tasted like Piotr's voice. It was almost night, and if you weren't home by night, you disappeared into a world from which there was no way to leave. There had been no gunfire that evening. Just quiet, and stale bread. Until, we heard something we had never heard before. 'Put-a-put-a-put-' and Father spoke. 'Piotr found something.' And indeed, Piotr had. We opened the curtain, and the three of us looked down into the street, and there he was. Piotr was home, and he had found a motorcycle. It was small, and it wasn't running right, but he had brought it home. Under the window, nine stories down, he looked so small. 'Father-' he called out. 'Look what I found! But it doesn't run right and I need help carrying it up the stairs.' Father's face lit up, glowed, and became happy. We were afraid he might leap out the window. 'My coat,' he said, and flew out the door like a starling."

And here she got quiet. She ran her fingers through my hair. Her eyes were big and wet. Her mouth formed shapes that spoke for her.

"The last things I remember are sounds. The streetlights turned on. Like a hum. The put-put-put of the little motorcycle. My father pounding down the stairs. Piotr, suddenly sounding like a small boy, the small boy he really was, 'father, I didn't know if you could fix it-' A flash. Sometimes you can hear a flash. And between the flash and the gunshot, Mother pulled us to the floor. A second flash, a second gunshot. Boots on the dirty street. I remember the way the floor felt, dusty and rough and without hope. The window was open and the curtains moved with the souls of Father and Piotr, who had suddenly become part of the wind. There was a knock on the door. I hid under the table. Mother kissed the top of my head. She walked into the hallway and she is walking still. I waited until morning. They had left the motorcycle, Piotr's motorcycle, between two pools of blood, soaking into the broken pavement. I ran to it. I pushed one hand into the puddle that had been Piotr, and the other into the puddle that had been Father. It was sticky, and sandy, and warm because the sun was up. Put-put-a-put-put... I rode Piotr's motorcycle across cities, countries, rivers, and oceans..."

Some stories finish themselves, and slip away like cigarette smoke, and smell bitter but comforting but too real to have happened. This one would have ended "...all the way to you." But I kissed her before she could finish. She tasted like blood and sand and gunpowder. The sun was coming up, and there were sounds starting outside our window. A man selling papers. A small dog barking at the smell of breakfast. The dull mechanical rotation of the Earth, grinding against everything that begs it to stop. And somewhere, far off, there was a put-a-put of a small motorcycle, driven by a boy running an errand for his family.

Monday, June 15, 2009

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

You do have a way....I can't imagine a whole book when just this page made me cry!

Post a Comment